Thermonuclear Ignition of Stars and the Nature of Dark Matter |

|

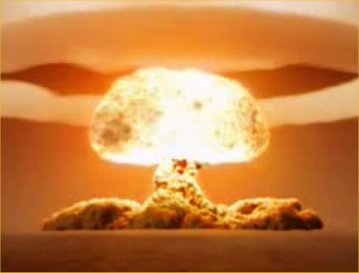

At the beginning of the 20th century, understanding the nature of the energy source that powers the Sun and other stars was one of the most important problems in physical science. Initially, the idea was that as the dust and gas collapsed to form a star, it would heat. In other words, gravitational potential energy would be converted into heat. Soon, however, calculations were made showing that the energy released would only be sufficient to power a star for a few million years at most and certainly life has existed on Earth for a longer time. The discovery of radioactivity, especially thermonuclear fusion [1], and the developments that followed led to the idea that thermonuclear fusion reactions power the Sun and other stars [2, 3]. Thermonuclear fusion reactions are called “thermonuclear” because temperatures on the order of a million degrees Celsius are required. The principal energy released from the detonation of hydrogen bombs comes from thermonuclear fusion reactions. The high temperatures necessary to ignite H-bomb thermonuclear fusion reactions comes from their A-bomb nuclear fission triggers. Each hydrogen bomb is ignited by its own small nuclear fission A-bomb. |

|

Strangely, astrophysicists have continued to make the same assumption to the present, although clearly there have been signs of potential trouble with the concept. Heating by the in-fall of dust and gas is takes place at the surface of the forming star. This heating is off-set by radiation from the surface, which is a function of the fourth power of temperature, in other words, T times T times T times T, which for T = 1,000,000 becomes a huge loss factor. |

|

After demonstrating the feasibility for planetocentric nuclear fission reactors [8, 9], including Earth’s georeactor, J. Marvin Herndon, pictured at left, proposed that thermonuclear fusion reactions in stars, as in hydrogen bombs, are ignited by self-sustaining, neutron induced, nuclear fission [10]. |

|

The idea that stars are ignited by nuclear fission triggers opens the possibility of stellar non-ignition, a concept which may have fundamental implications bearing on the nature of dark matter [10] and much, much more. The old idea about stellar ignition by heat produced during gravitational collapse developed before nuclear fission was discovered and no one, for more than six decades, until Herndon [10], thought to question the concept. It is well to recall that science is a logical process, not a democratic process. New ideas begin with a single individual and then diffuse, sometimes slowly, throughout the scientific community. The idea that natural fusion reactions are ignited by natural fission reactions is a fundamentally new and revolutionary concept with profound astrophysical implications. |

|

YouTube Video: Lighting the Stars (click here) The nature of star ignition has been misunderstood since a mistake was made in the 1930s and subsequently built upon J. Marvin Herndon reveals the mistake and describes the rationale for his correcting it. (click here for notes and references) |

| References | |

| 1. |

Oliphant, M. L., Harteck, P., and Rutherford E., Transmutation effects observed with heavy hydrogen. Nature, 1934, 133, 413. |

| 2. | Gamow, G. and E. Teller, The rate of selective thermonuclear reactions. Physical Review, 1938, 53, 608-609. |

| 3. | Bethe, H. A., Energy production in stars. Physical Review, 1939, 55(5), 434-456. |

| 4. | Hahn, O. and Strassmann, F., Uber den Nachweis und das Verhalten der bei der Bestrahlung des Urans mittels Neutronen entstehenden Erdalkalimetalle. Die Naturwissenschaften, 1939, 27, 11-15. |

| 5. | Hayashi, C. and Nakano, T, Thermal and dynamic properties of a protostar and its contraction to the stage of quasi-static equilibrium. Progress in Theoretical Physics, 1965, 35, 754-775. |

| 6. | Larson, R. B., Gravitational torques and star formation. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 1984, 206, 197-207. |

| 7. | Stahler, S. W., The early evolution of protostellar disks. Astrophysical Journal, 1994, 431, 341-358. |

| 8. | Herndon, J. M., Nuclear fission reactors as energy sources for the giant outer planets. Naturwissenschaften, 1992, 79, 7-14. |

| 9. | Herndon, J. M., Feasibility of a nuclear fission reactor at the center of the Earth as the energy source for the geomagnetic field. Journal of Geomagnetism and Geoelectricity, 1993, 45, 423-437. (click here for pdf) |

| 10. | Herndon, J. M., Planetary and protostellar nuclear fission: Implications for planetary change, stellar ignition and dark matter. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 1994, A455, 453-461. (click here for pdf) |

By 1938, the idea of thermonuclear fusion reactions as the

energy source for stars had been reasonably well developed by Hans Bethe,

pictured at right, and by others. But at that time nuclear fission

had not yet been discovered [4]. At the time, physicists, just assumed that the

million-degree-temperatures necessary for stellar thermonuclear ignition would

be produced by the in-fall of dust and gas during star formation.

By 1938, the idea of thermonuclear fusion reactions as the

energy source for stars had been reasonably well developed by Hans Bethe,

pictured at right, and by others. But at that time nuclear fission

had not yet been discovered [4]. At the time, physicists, just assumed that the

million-degree-temperatures necessary for stellar thermonuclear ignition would

be produced by the in-fall of dust and gas during star formation.