Richard D. Oldham's Discovery of the Earth's Core |

|

In 1798, from his measurements of gravitational attraction, Lord Cavendish, illustrated at left, reported the density of Earth to be 5.48 times the density of water, a result quite close to 5.53, the modern measured value [1]. One hundred years later, Emil Wiechert, pictured at right, realized that the density of the Earth is greater than the density of rock, meaning that the Earth cannot be composed entirely of rock. In 1898, Wiechert suggested that the Earth might be like a giant meteorite with a core of nickel-iron metal which had settled to the center like iron settles from slag on the hearth of an iron mill. Wiechert justified his idea with calculations showing that the Earth’s density could be explained if the Earth has a core of nickel-iron metal (like the iron meteorites he had seen in museums) surrounded by a shell, or mantle, of rock [2]. |

|

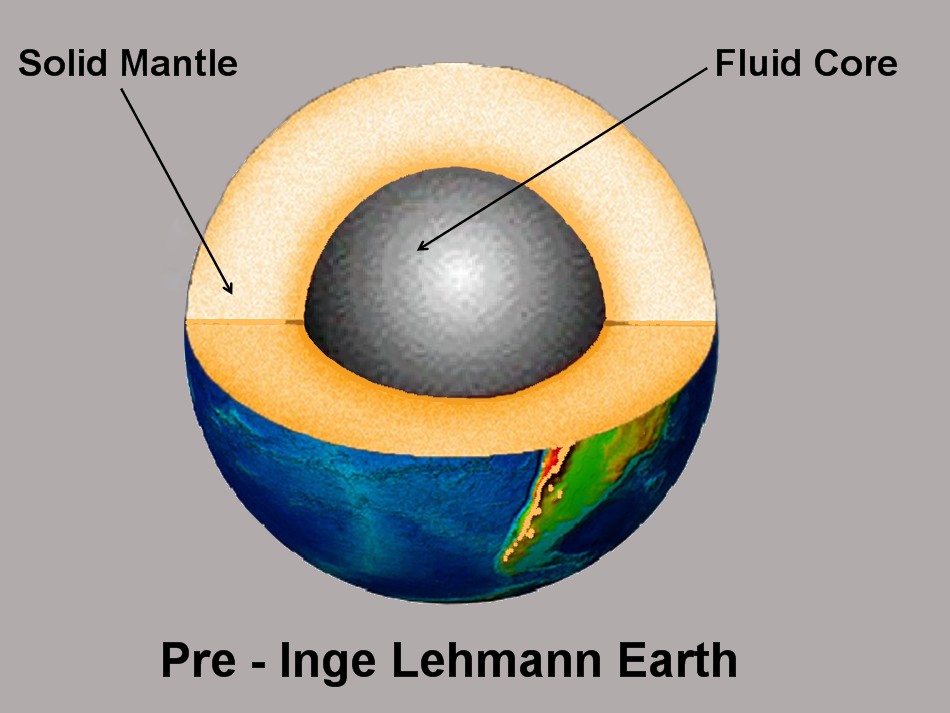

By the early 1930s, seismologists had established the size of the Earth's core and had shown that it is liquid, because it is unable to transmit shear waves. As 1936 approached, the interior of Earth seemed rather simple, like the representation at right, consisting of a fluid core surrounded by a solid rock mantle, and topped by a very, very thin crust. But then, a mystery was discovered. Earthquake waves were found where it was thought they should not be found. Inge Lehmann solved that mystery and discovered an object within the fluid core, the inner core [4]. |

| References | |

| 1. |

Cavendish, H., Experiments to determine the density of Earth. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1798, 88, 469-479. |

| 2. | Wiechert, E., Über die Massenverteilung im Inneren der Erde. Nachr. K. Ges. Wiss. Goettingen, Math-Kl., 1897, 221-243. |

| 3. | Oldham, R. D., The constitution of the interior of the Earth as revealed by earthquakes. Q. T. Geol. Soc. Lond., 1906. 62, 459-486. |

| 4. | Lehmann, I., P'. Publ. Int. Geod. Geophys. Union, Assoc. Seismol., Ser. A, Trav. Sci., 1936, 14, 87-115. |