Consequences of the Discover Magazine Article |

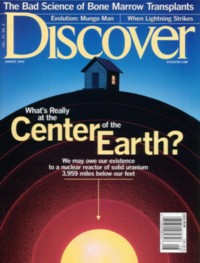

With publication of the August 2002 issue of Discover Magazine, people throughout the world became aware of Herndon's concept of a nuclear fission georeactor at the center of the Earth. Suddenly, people everywhere and scientists too learned about the georeactor. There was interest at all levels of society. Spontaneous debates erupted on the Internet. Scientists became interested in the subject, such as K. R. Rao, who wrote a paper entitled, “Nuclear reactor at the core of the Earth! - A solution to the riddles of relative abundances of helium isotopes and geomagnetic field variability” (click here). The Swiss senior nuclear reactor engineer, Walter Seifritz, verified the georeactor calculations (click here) and began to have discussions with other nuclear scientists about the implications. There were media interviews, invitations to lecture on the subject in America and in Europe, articles in print, for example, in The Washington Post, The San Francisco Chronicle, The Sunday Times of London, Die Welt, Neue Bürcher Zeitung, The Deccan Herald, and many others, and as well in broadcast news features, such as Paul Harvey News and Comment. There were magazine articles in Science & Vie, Newton, Sciences & Avenir, New Scientist, and elsewhere. But two in particular show the extent of interest among ordinary people: The German magazine Hör Zu, contained an article about the georeactor, as well as the complete schedule of German television programs, and; Japan Weekly Playboy carried an in depth article about the georeactor, along with cartoon features, sports features, and photos of beautiful young women. Soon one thing became apparent: People everywhere want to learn about their world, and about the debate that should be a natural part of science. Many ordinary people began asking the questions that scientists should be asking. For example, an environmental economist from Ecuador asked whether the El Niño might in some way be related to variations in georeactor output. A former World war II nurse wrote a fiction book, entitled "Life in a Nuclear magnetic Web" in which Herndon's theory of a nuclear reactor within the Earth's core is, according to author Bonnie L. Harter, "interwoven into this science fiction story in the hope that more scientists and students will study it." For more information, please click here. After learning about the georeactor as a consequence of a summer intern's lunch-time seminar at Bell Laboratories, R. S. Raghavan, a neutrino expert at Bell Laboratories authored a paper, entitled “Detecting a Nuclear Fission Reactor at the Center of the Earth” (click here). Raghavan’s paper, posted on the Internet physics archive, arXiv.org, stimulated intense interest worldwide, with groups in Russia, Italy, and the Netherlands figuring prominently in the early appreciation georeactor-produced anti-neutrino detection and ultimately leading to innovative new technological concepts. Russian scientists expressed well the importance: “Herndon’s idea about georeactor located at the center of the Earth, if validated, will open a new era in planetary physics” (click here). For a brief time, it looked as if science was beginning to function as it should, with openness to new ideas, with debate and discussion, and with efforts being made to attempt validation. Then along came the science-barbarians. Raghavan told a European that his paper had been rejected by two journals, Physical Review Letters and another, because – paraphrasing – one or more secret reviewers objected to Herndon's georeactor concept. To the European, the implied warning was clear: Cite Herndon’s work and your own papers might not get published. If those anonymous reviews were to be subpoenaed by the U. S. Justice Department, the odds are great they would show blatant misrepresentation by university faculty members, principal investigators of U. S. Government research grants to their respective universities. There is something fundamentally wrong with an institution accepting taxpayer money to conduct scientific research and at the same time allowing its faculty/employees to suppress advances in science with phony-baloney, made in secret reviews . But that is an every-day occurrence in American universities. There is much, much more to the story. Real scientists appreciate advances in science, as advances generally open the door to new discoveries. Science is about truth, not suppression, not misrepresentation, not to the scientific community and not to the general public. |